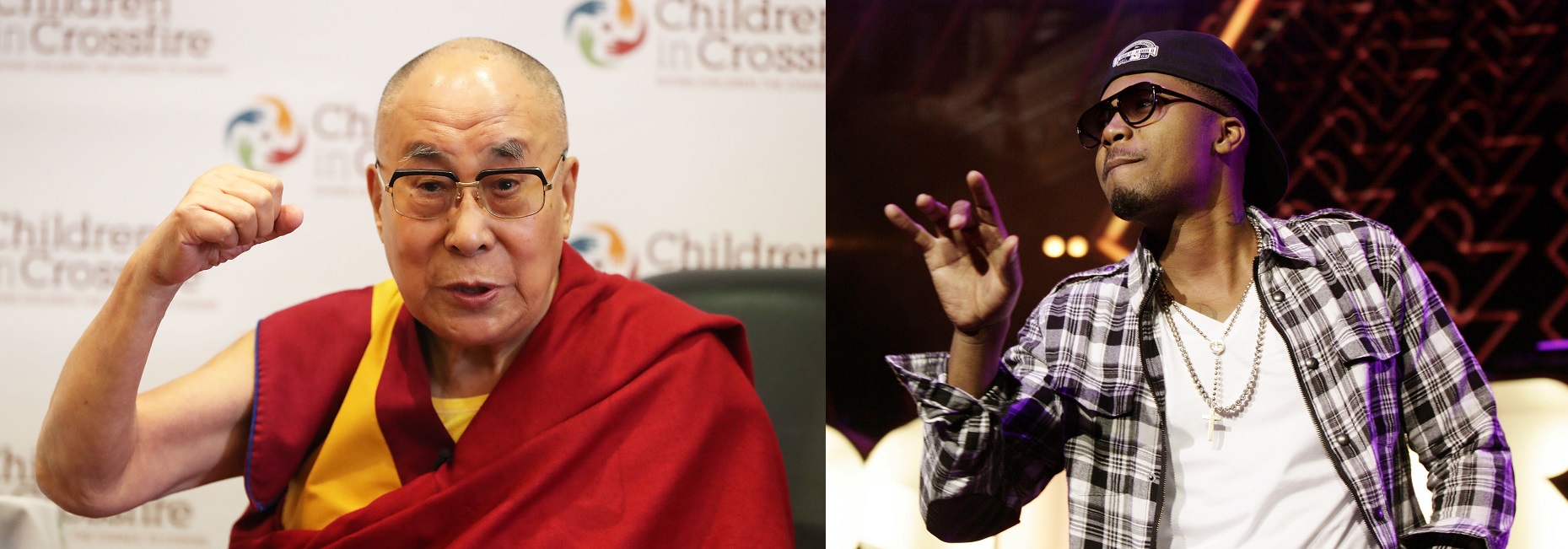

Sleep. “The best meditation,” according to the Dalai Lama. “The cousin of death” is the slightly less cheery opinion of veteran American rapper Nas.

Whether your view chimes better with that of the Tibetan spiritual leader, the controversial musician, or somewhere in between, the fact is we all need it – particularly during the last year.

The coronavirus pandemic has played havoc with almost every facet of our waking lives, from work, education and finances, to travel, leisure and social freedoms.

And it seems it has also had a knock-on impact on our slumber time, too.

We spoke to Professor Mark Blagrove, a leading expert in sleep and dreaming at Swansea University’s Department of Psychology, on how much sleep we need and why, and what to do if we have nightmares…

Why is sleep important?

Despite the temptation to squeeze every last waking second out of one of the most depressing and, frankly, boring years in many people’s lives, the fact is humans need sleep.

One of the reasons is biological, as sleep protects the brain from conditions such as Alzheimer’s by flushing out harmful toxins, Blagrove says. But it also allows us to connect the memories during the day and sieve through which ones are important. “It allows us to summarise what we learnt,” according to the expert, “rather than storing all of the memories during the day.”

How much sleep is needed then?

History is peppered with world leaders famed for their relatively brief periods of shut-eye. But the likes of Donald Trump and Margaret Thatcher – both of whom were said to rely on around four hours’ sleep per night – are in the minority.

Blagrove recommends sleeping for at least six or seven hours a night. “If you get too little sleep, it does affect your mood, how fast you can think, and your ability to learn,” he says. “If people are getting far less sleep than they need, that will show.”

So how has the coronavirus pandemic affected sleep patterns?

It is not all bad. People working from home may have found the precious time previously spent commuting can be redistributed elsewhere – including sleep.

Others, however, will have found that the stresses and strains of life under lockdown will keep them up all night.

“People may be having less sleep because of the worries they have in the working day,” Blagrove says. “One of the causes of insomnia is resentment – if people feel resentful of others, it can add to insomnia.

The effects of the pandemic will be that some people have been badly hit, while others will not notice or indeed benefit.”

OK then – how do we give ourselves a fighting chance of getting our precious sleep allowance?

The standard recommendation for people who are not sleeping too well is to stick to a set wake-up time rather than trying to recoup sleep they may have lost by sleeping in.

So, that means if you wake up at 7am five days of the working week, you ought to try to stick to it at the weekends. Those with young children may wish to adjust the start time accordingly.

“The body clock will wake you up and get you ready for bed, by starting to decrease the body temperature when ready for bed,” says Blagrove.

“If you have a chaotic sleep life, then that body clock isn’t so robust.”

Blagrove also recommends trying to reduce the number of things bothering a person before they get their head down.

“Let go of the things that are really vexatious for people at the moment,” he says. “Let it go in the half an hour before sleep.”

What about booze and scrolling Twitter – will that keep me up at night?

Alcohol is a curious one. While it can make someone fall asleep quicker, it metabolises during sleep so can often result in waking up four or five hours later.

“High levels of alcohol – aside from whatever else they are good or bad for – they’re not good for your sleep, even if people think they have loads of worries and it will knock them out,”

Blagrove says. “It’s not the best way of doing so.”

Mobile phones and tablets can also have a negative impact, he says, by stimulating the brain with mini bursts of information rather than relaxing it.

Instead, try reading. “Books take more thoughtfulness,” Prof Blagrove says, “they can be less problematic because they are more relaxing. You have to take all the words in and contemplate them.”

Is it alright just to binge-sleep at the weekend?

Sadly, it seems that consistency is key to a healthy sleep pattern, and that means trying to get to bed at the same time each night, rising the same time the following morning.

“If you really are regular for the majority of the nights, it may be not so bad to have a night that’s different,” Blagrove says.

“On a regular basis, it’s not that helpful to keep disrupting your body clock by having a much later bedtime.”

Getting sleep isn’t a problem – it’s what happens to my dreams that is the worrying part. Any tips?

Changes to people’s lives have, anecdotally, seemed to have an impact on people’s dreams. “If people are having a distressing waking life, it may present in their dreams,” Blagrove said.

Thankfully, there are some tried and tested tips on how to reduce nightmares. “Share your dreams, tape record them and tell to someone later if necessary,”

Blagrove says. “The other option is to think about the whole nightmare, and think about what change you’d like to make, and imagine the changed element for 10 minutes.

“It’s called re-scripting or image rehearsal therapy – the altered version stops your brain during the night automatically going back to that distressing version.”