Ranking world number one in both singles and doubles, winning a total of 17 Grand Slam titles, remaining the only male player to win more than 70 titles in singles and doubles, and still staying active in retirement, John McEnroe is renowned as one of the best tennis players in history.

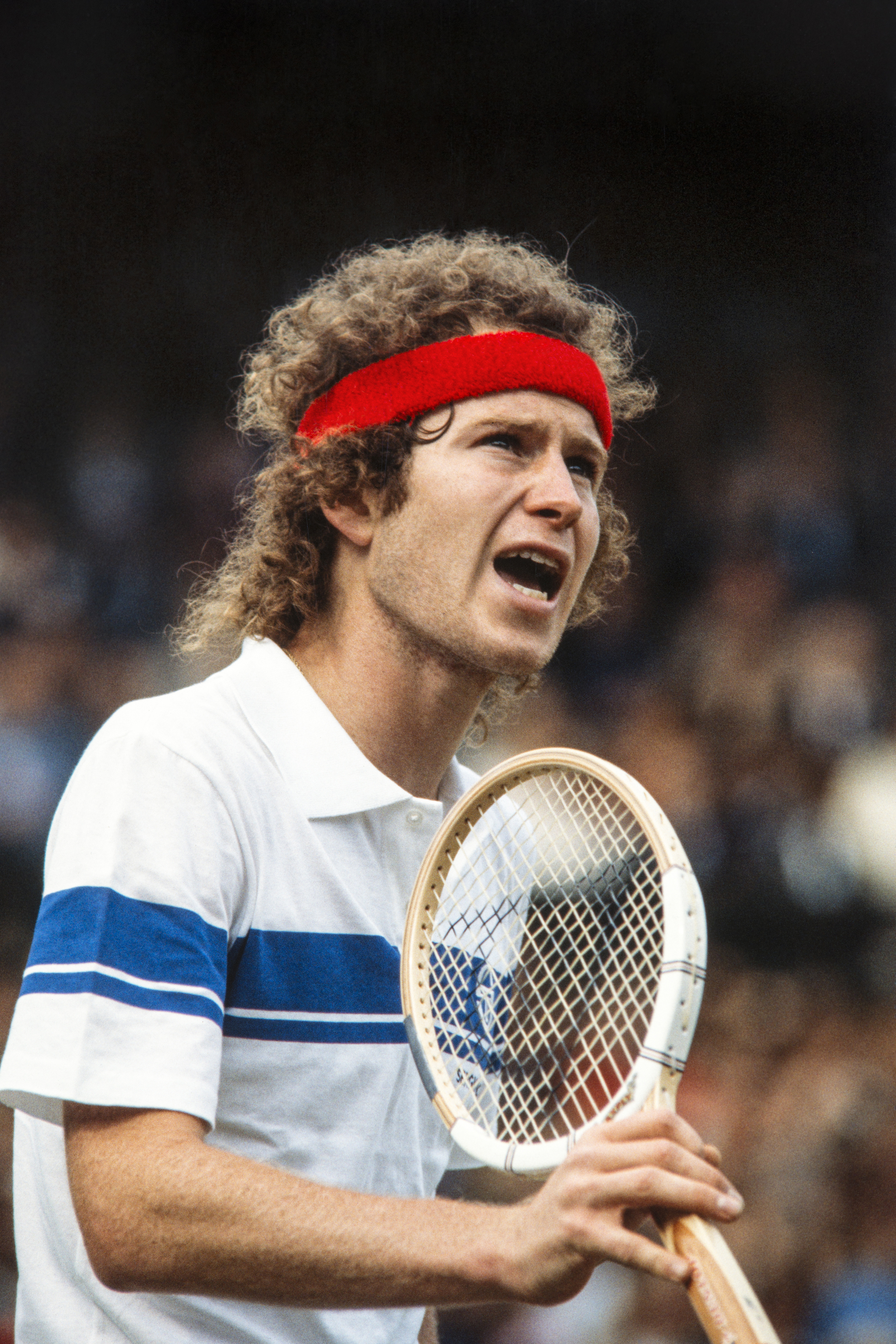

However, his fiery temper and on-court tantrums also earned him infamy in the sport, with his biography in the International Tennis Hall of Fame recognising his “boisterous outbursts” as prominently as his “considerable skill and finesse”.

Now, in McEnroe, a documentary film about his career and life off the court, the veteran sportsman is seeking to set the record straight. It’s a revealing look at the man holding the racquet, at his hopes, dreams, fears and pressures – both personal and professional – on his journey to become world champion.

The McEnroe I chat with over Zoom seems a different man from the one I’d seen in video clips shouting ‘You cannot be serious!’ at umpires. Silver-haired at 63 years of age, wearing a sharp denim jacket and a T-shirt, he’s composed, introspective and remarkably candid in his honesty.

In the documentary directed by Barney Douglas, whose credits include cricket films The Edge and Warriors, McEnroe says he was encouraged to be ruthless and intense, not letting his guard down even to enjoy the moment – “and I hated that”.

I wonder how different he thinks his career and reputation might have been if he hadn’t felt such incredible pressure – which he describes in the documentary as a “burden” – both from himself and from others throughout his time on the court.

“That’s a good question, and one that’s unanswerable for the most part,” he responds, clearly having spent some time ruminating on it.

“Probably, had I been able to focus more on my tennis… I’d probably have different colour hair, my hair wouldn’t be quite as white now!

“I probably would have won more, I believe. I also probably would have been more boring – so perhaps this documentary that they made wouldn’t have been made.

“Maybe had a few more records – I’ve lost pretty much all the ones I did have due to these three amazing players, among others, that have come along,” he adds, referring to the Big Three – Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic, who are widely considered the three most successful male players in tennis history.

“You always want to maximise your potential. I don’t think I quite did that. But at least I got pretty close.”

During the process of reflecting on his formative decades, both in terms of his career and personal life, McEnroe says he was “more interested in the overall journey” than “looking back to what I coulda, woulda, shoulda done in certain matches”.

“I don’t think that’s instructive, at this point,” he says, shrewdly.

“And I don’t think it sets a good example for my kids, or other kids, that I’m thinking about what I should have done instead of what I did do.”

He praises young Japanese tennis star Naomi Osaka for speaking out about the mental health challenges of competing as a high-level athlete – she withdrew from the 2021 French Open and Wimbledon tournaments to care for her wellbeing after refusing to attend any press conferences at Roland-Garros due to mental health concerns – adding that her actions offered him “food for thought”.

“She’s not the first person that experienced this, but she’s been more upfront about it,” McEnroe says.

“I went through things where I felt it was overwhelming and difficult. And feeling like I wasn’t handling it well, and feeling like it’s too much to ask to an individual.

“It’s important to have people around you that you can trust… people that are there to keep your head on straight, and then nurture you in a way that allows you to go out and give the type of effort you need to consistently give on a court.”

It’s clear that McEnroe has taken his retirement as an opportunity to reconsider the legacy he wants to leave behind, to reconstruct the persona that people will remember him for – particularly his family and his children.

“I feel like I’ve become like an ambassador to our sport, in a way,” he says.

“That’s what I’d like to look at myself as, because I’m an ex-player who knows what it’s like to be on Centre Court, and hopefully can give free advice to anyone – not a lot of people call me, by the way – but nonetheless, I feel like I could hopefully be helpful if they need it in their journey.

“Because it’s taken me a long time to get to a place where I feel somewhat at peace and feel like, OK, the direction I’m heading, I’m proud of.”

I ask him what he hopes people will learn about him from watching the film, and his answer is surprisingly intimate.

“I think just, you know, that we’re human beings, and that I go through the same type of questions that a lot of people have,” he says.

“You know: ‘How are you going to deal with the end of a marriage?’ Which is tough – a lot of people go through divorces, you have kids, that becomes your number one priority. ‘How are you going to navigate that into a second marriage, with more kids?’

“I love having a lot of kids around, but it certainly is something that – I mean, there’s nothing more exhilarating, nothing more difficult.

“And then having a second chance, which I feel like I got. I ended up meeting my wife Patty (Smyth), and she did something that I think was all you could ask of a partner: allowing that person to flourish and be the person he wants to be. She let me be me.”

McEnroe is in cinemas now.