Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer, affecting over 55,000 people each year.

As the most common type of cancer, there is a lot of readily available information online, from how to check yourself, to what to look out for. Navigating all this can be daunting.

To help cut-through some of the noise, Nuffield Health’s GP National Lead, Dr Unnati Desai have answered ten of the most commonly asked questions surrounding breast cancer.

1: Are most breast lumps cancerous?

A lump is not necessarily a sign that you have breast cancer. Roughly 80% of lumps in breasts are caused by benign (noncancerous) changes, cysts, or other conditions. However, if you do find a lump, it’s essential that you get it checked by a GP, just to be sure.

2: Does breast cancer always present itself in the form of a lump?

Many people examining their breasts wrongly believe they should be looking exclusively for lumps.

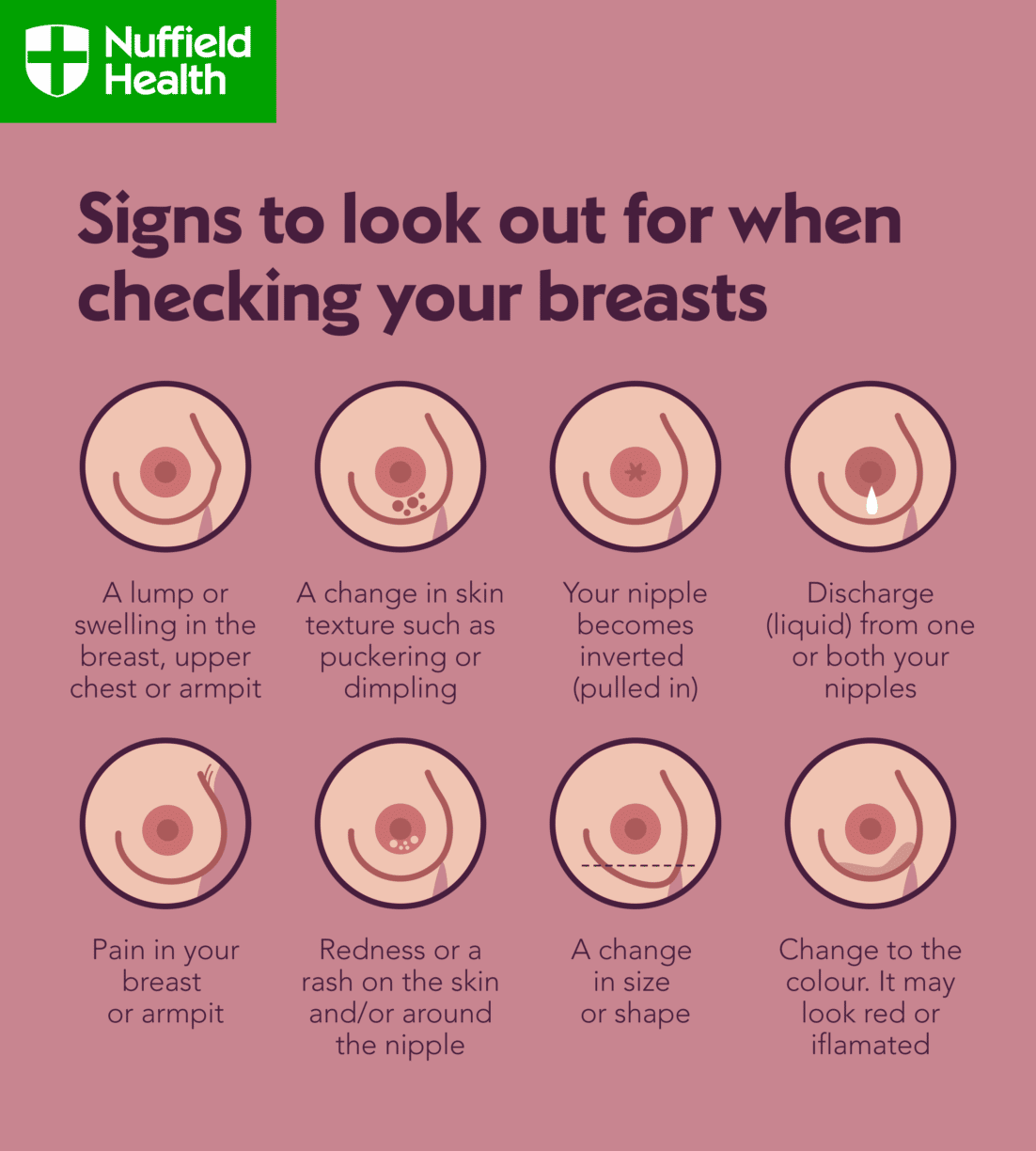

There are other changes in the breasts to look out for, such as:

- changes to breast skin (discolouration, redness, irritation or scaliness, thickening or dimpling)

- changes to the shape or size of the breasts

- breast or nipple pain

- nipple inversion or discharge

- swelling under the armpit or around the collar bone

If you notice any change to your breast tissue, it is important to see a GP for a full assessment.

3: What can you do if you’re at risk for breast cancer, aside from look out for the signs?

Self-examination is key. You are more likely to notice change to your breast tissue if you examine yourself regularly. Self-examination is best done monthly, and if menstruating should be done 2-3 days after menstrual bleeding finishes.

In addition, maintaining a healthy weight, exercising regularly, keeping alcohol consumption low and not smoking all help to lower the risk of developing breast cancer.

4: Are only people with a family history of breast cancer at risk?

No – roughly 70% of women diagnosed with breast cancer have no identifiable risk factors for the disease. But there are family-history risks, these are:

- One first degree female relative diagnosed with breast cancer aged younger than 40 (a first degree relative is your parent, brother or sister, or your child).

- One first degree male relative diagnosed with breast cancer at any age.

- One first degree relative with cancer in both breasts where the first cancer was diagnosed aged younger than 50.

- Two first degree relatives, or one first degree and one second degree relative, diagnosed with breast cancer at any age (second degree relatives are aunts, uncles, nephews, nieces, grandparents, and grandchildren).

- One first degree or second degree relative diagnosed with breast cancer at any age and one first degree or second degree relative diagnosed with ovarian cancer at any age (one of these should be a first degree relative).

- Three first degree or second degree relatives diagnosed with breast cancer at any age.

5: Does wearing an underwire bra increases your risk of getting breast cancer?

No – claims that underwire bras compress the lymphatic system of the breast, thereby causing toxins to accumulate and increasing the risk of breast cancer, are not backed up by science.

The consensus is that neither the type of bra you wear nor the tightness of your underwear or other clothing has any connection to breast cancer risk.

6: Does wearing antiperspirant increases your risk of getting breast cancer?

No – there are claims that parabens, used as preservatives in some antiperspirants, have weak oestrogen-like properties and may contribute to breast cancer development. However, no cause-and-effect connection between parabens and breast cancer has been established.

7: Do smaller breast have less chance of getting breast cancer?

The risk of breast cancer occurring is not related to the size of the breasts. However, size may impact detection. The larger or denser the breast, the more meticulous self-examination needs to be to ensure all the deeper tissue is felt.

In smaller breasts, or when breast tissue density is less, changes may be more noticeable. It’s important to check your breast regularly, regardless of your breast size and density, to pick up any changes sooner.

Mammographers are specially trained to ensure people of all sizes can be screened. More important than size is the type of tissue the breast is made of. Very dense tissue, which shows up white on a mammogram, can make it difficult to detect small cancers.

8: Can caffeine cause breast cancer?

There has been no causal connection found between drinking caffeine and getting breast cancer. So far, it’s inconclusive whether breast soreness may be linked to caffeine.

9: Are people with lumpy breasts (fibrocystic breast changes) more at risk of developing breast cancer?

In the past, people with lumpy, dense, or fibrocystic breasts were believed to be at higher risk of getting breast cancer, but science has since concluded that there is no connection after all.

However, when you have these types of breasts, it can be trickier to differentiate normal tissue from cancerous tissue, so it’s important that you report any changes to your GP.

10: Do mammograms expose you to so much radiation that they increase your risk of cancer?

While it’s true that radiation is used in mammography, the amount is so small that any associated risks are tiny when compared to the huge preventive benefits gained from the test.

Mammograms can detect lumps well before they can be felt or otherwise noticed, and the earlier that lumps are caught, the better one’s chances of a positive outcome.

Mammograms are not recommended in younger people as they generally have denser breast tissue, which makes it difficult to detect abnormalities. In this instance, the dose of radiation from a mammogram cannot be justified to warrant the use of mammograms for routine screening.

If you would like to speak to a healthcare profession and get your breasts checked, you can book in for a Female Health Assessment at Nuffield Health.